5 key works from the Arts Council Collection

To celebrate the 75th birthday of the Arts Council Collection, David Trigg charts its history and highlights the ongoing impact of five key works acquired for the collection with Art Fund support.

Marking 75 years of collecting in 2021, the Arts Council Collection (ACC) is the largest national loan collection of modern and contemporary British art in the world. Established along with the Arts Council of Great Britain in 1946, from what since 1940 had been the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA), it began with a modest group of paintings. Today, the collection holds an outstanding array of more than 8,000 works in a diverse range of media by more than 2,000 artists, including Tracey Emin, Lucian Freud, Mona Hatoum, Barbara Hepworth, Anish Kapoor and Grayson Perry. Its principal aim is to promote the appreciation of contemporary art, which it now achieves through an extensive programme of touring exhibitions, exhibition loans, long-term loans, publications and, more recently, digital offerings such as the Art Crush app, a playful platform that allows anyone with a smartphone or tablet to explore and build a virtual collection.

Even though the ACC is managed by the Southbank Centre in London, the majority of its work is shown outside the capital. Each year more than 1,000 individual loans are made to venues, reaching the broadest possible audience across the UK. ‘Having a high-profile artist in the gallery always engenders a sense of pride in our local audiences,’ says Paulette Brien, a curator at Blackpool’s Grundy Art Gallery. ‘As we area relatively small team with restricted resources, the ACC enables us to deliver shows of a scale that we would not be able to do alone.’

Public ownership is central to the ACC. ‘The collection belongs to everyone and exists to be shared and discussed,’ says Natalie Rudd, the ACC’s senior curator. ‘Our remit is for our artworks to be seen as widely as possible.’ Beyond museums and galleries, the ACC lends to hospitals, libraries, charities and universities – anywhere with a public space for art. Chances are you have encountered works from the collection without being aware of it. As Rudd puts it: ‘The Arts Council Collection reaches spaces that other collections don’t reach.’

The ACC continues to grow through its annual purchases of works by artists living in Britain, with a particular focus on those in the early stages of their career. A changing committee of eight individuals oversees the acquisitions, with bias avoided through the appointment of external advisers – an artist, a writer and a curator – for a fixed tenure of two years. ‘This has remained very consistent throughout the collection’s history,’ explains Rudd. ‘What has changed, however, is a diversification of that panel. In the earlier days there tended to be a narrower demographic, but from around 1980 onwards we had a much broader representation of artists, writers and curators sitting on the panel, which allowed diverse voices to enter the collection and has had a lasting impact on the type of work that we acquire.’

For particularly ambitious acquisitions, the ACC receives financial support from external partners, including Art Fund. ‘Partners are incredibly important because they enable us to acquire works that would otherwise be outside our reach,’ says Rudd. ‘Over the years Art Fund and others have helped purchase some really key works, which we have been able to share nationally and preserve for future generations.’

Antony Gormley, Field for the British Isles, 1993

Acquired in 1995 with support from Art Fund and the Henry Moore Foundation

The arresting sight of some 40,000 miniature terracotta figures staring back at you is not easily forgotten. More than 500,000 people have so far experienced Antony Gormley’s Field for the British Isles (1993). Since the work entered the Arts Council Collection in 1995, it has been shown in venues as diverse as a disused railway shed in Gateshead, a Shrewsbury church, cathedral cloisters in Salisbury and Gloucester, a 15th-century barn at Torre Abbey in Torquay, and at art galleries from St Ives to Scunthorpe.

The vast sea of rudimentary figures that comprise this epic work were handmade by a 100-strong group of volunteers, aged seven to 70, from St Helen’s, Merseyside. Just as the production of Field for the British Isles was collaborative, so too is its installation, with local volunteers taking a week to set up the work at each venue.

In 2019, on the eve of Brexit and amid growing fears about climate change, Field for the British Isles was displayed at Firstsite in Colchester, Art Fund Museum of the Year 2021. For director Sally Shaw, the work represents future generations and the responsibility we all have to this ‘field of gazes’. ‘With the figures in Field mirroring the 40,000 children and young people living in Colchester, it was a chance for visitors to view this entire community before them – and consider our agency and collective creativity in responding to the challenges and opportunities we face together,’ Shaw says. The exhibition attracted more than 48,000 people, and many were impressed by the collaborative nature of the work. ‘I think that is what art should be all about, that we have public ownership of it,’ said one visitor.

Being a part of the ACC ensures that ambitious works such as Field for the British Isles remain accessible for many generations to come. As Gormley has said: ‘It’s a precious and wonderful thing that this work continues to be cared for, continues to be seen, and continues to be relevant through the agency of the Arts Council Collection.’

Roger Hiorns, Seizure, 2008-13

Acquired in 2011 with support from Art Fund and the Henry Moore Foundation

In 2008, when Roger Hiorns pumped 75,000 litres of liquid copper sulphate into an empty council flat in south London, he could not have imagined that the resulting blue crystalline interior would still be enchanting visitors more than a decade later. Originally commissioned by Artangel and the Jerwood Charitable Foundation, Seizure is a strangely beautiful yet simultaneously menacing work with large, sparkling crystals covering the walls, floor, ceiling and bath of the former home.

At its first location near Elephant and Castle, the work became a site of pilgrimage, attracting thousands of visitors. After its closure to the public in 2010 and with the estate in which it was located facing demolition, Seizure was saved for the Arts Council Collection. After being successfully extracted from the social-housing block, it was transported to Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where, under a 10-year loan agreement, it is exhibited within a specially designed container-like structure.

‘The spine and the backbone of national art is the Arts Council Collection,’ Hiorns has said. ‘It collects artists at a young age and supports them at a tender time, [when they are] usually broke and up against it. Seizure was allowed to carry on by this enlightened ideal of a collection. “Saved for the nation” was always an epithet that seemed premature for an artist of my age, but they had the foresight to challenge orthodoxy and protect a work now beyond my reach.’

The work’s cult status has continued to grow at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where it remains incredibly popular. ‘It is such a unique installation,’ says Rudd. ‘Some people find it a really comforting space, like a sanctuary, while others find it quite grungy and threatening.’ Many visitors experience a jaw-dropping moment when they step into the work for the first time. ‘It’s a real highlight because it’s just so different from anything else that you’re probably ever going to see anywhere.’

Melanie Manchot, Dance (All Night, London), 2017

Acquired in 2017 with support from Art Fund

For the 2017 edition of London’s contemporary art festival Art Night, Melanie Manchot staged an ambitious outdoor dance event. Her 30-minute film, Dance (All Night, London) (2017), documents the proceedings, showing students and teachers from 10 east London dance schools as they parade through the streets before dancing the night away at Exchange Square, one of central London’s largest public spaces. Here, audience participation was encouraged through free dance lessons and a silent disco where people practised their newly learned moves to the vibrant rhythms of Cuban Rueda, Chinese Dance and Argentine Tango. Manchot has said that the project allowed her ‘to explore notions of collective agency – and collective joy – by inviting a diverse public to come together and participate in the production of an unchoreographed mass dance’.

The film was recently shown among the baroque grandeur of Beningbrough Hall for the exhibition ‘In the Moment: The Art of Wellbeing’. Curated by Helen Osbond and comprising works from the ACC, the show explored the benefits of art on wellbeing by encouraging visitors to ‘connect, get active, give, keep learning and take notice’. ‘It was important the exhibition brought about opportunities for the audience to explore artistic interpretations of these concepts in a way that promoted engagement,’ Osbond says. ‘Melanie’s work encapsulates this perfectly, creatively depicting how connecting with others and rhythmic activity benefits the head as well as the heart.’ Audiences at Beningbrough agreed: ‘After walking through the quiet spaces in the hall, the activity is energising,’ said one person. Another visitor commented that the work ‘makes you appreciate that physical activity helps mental health’.

The venue’s general manager, David Morgan, has said: ‘Displaying work from the Arts Council Collection has been an uplifting experience for our visitors. Art and beauty are crucial for everyone’s wellbeing and these works helped us to engage again with our audience as lockdown eased.’

Sarah Lucas, NUD CYCLADIC 7, 2010

Acquired in 2012 with support from Art Fund

The ambiguous, biomorphic forms of Sarah Lucas’ NUD CYCLADIC 7 (2010) have a curious, flesh-like quality that is suggestive of bodily limbs. The sculpture is one of a series from 2010 made with stuffed nylon tights, a material that Lucas has often used for her provocative works addressing gender and sexuality. ‘I thought there was something so human about them,’ she has said, ‘something quite sexy.’ Yet there is nothing discernibly male or female about this abstract figure, which simultaneously references the smooth forms of ancient marble statuary and the works of Modernist sculptors such as Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. The sculpture complements several other works by Lucas that are held in the ACC.

Thousands of people have seen the work in a diverse range of exhibitions across the UK. At the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, in 2012, for example, ‘Sarah Lucas: Ordinary Things’ presented the sculpture in the context of Lucas’ wider practice, while in 2013, at The Collection, Lincoln, it was juxtaposed with objects taken from the county of Lincolnshire’s archaeological holdings in ‘The World is Almost Six Thousand Years Old’. The work was also included in ‘The Weather Garden: Anne Hardy curates the Arts Council Collection’ at Towner Eastbourne in 2019. Here, Hardy placed NUD CYCLADIC 7 alongside 30 works exploring the interconnectedness between space, body and material.

More recently, it has been part of ‘Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women since 1945’, which opened at Yorkshire Sculpture Park earlier in 2021. The show is currently in Nottingham and will tour to Plymouth, Hull and Walsall. ‘On the one hand the sculpture is grotesque, on the other it’s quite serene and classical,’ says Rudd, also the show’s curator. ‘Visitors want to prod it and test it materially, which, of course, they’re not allowed to do. People just find this work fascinating.’

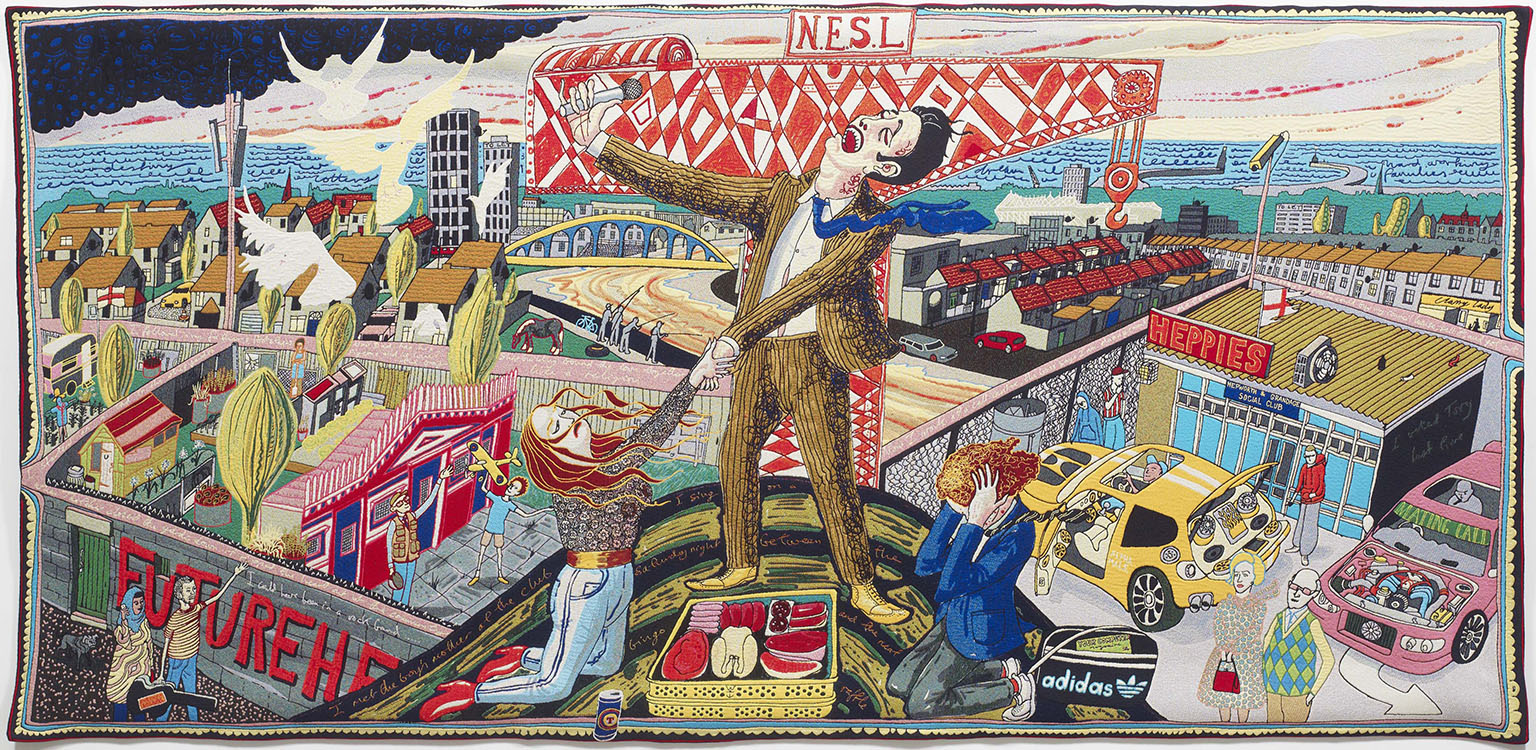

Grayson Perry, The Vanity of Small Differences, 2012

Acquired in 2012 with support from Art Fund, one of several funders

Grayson Perry produced The Vanity of Small Differences in 2012 while filming the Channel 4 television series All in the Best Possible Taste, which focused on the emotional investments we make in the things we consume, use and surround ourselves with. Inspired by William Hogarth’s satirical painting series A Rake’s Progress (1732-34), the six colourful tapestries are a wryly observed exploration of class mobility in modern Britain and its influence on aesthetic taste. They tell the story of a fictional character, Tim Rakewell, as he climbs the social ladder, from humble working-class beginnings to making his fortune in computer software. Crammed with cultural references and also allusions to religious art of the Renaissance, the detailed scenes include many of the characters, incidents and objects that Perry encountered while filming in Sunderland, Tunbridge Wells and the Cotswolds.

In 2014 the tapestries toured the UK. Over the course of the year, they were shown at Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens, Manchester City Art Gallery, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery, and the Tudor-Jacobean mansion of Temple Newsam, Leeds. More than 400,000 visitors came to see Perry’s works, and some of them were profoundly moved: ‘They made me cry, they have so much meaning and symbolism,’ said one visitor in Sunderland, and a local GP similarly commented: ‘I laughed, I cried; I saw in these works the passion and pathos that I see every day in my work.’

The Vanity of Small Differences has since toured the country twice more, from Canterbury to Rochdale, where many venues reported record-breaking attendance, such as Bath’s Victoria Art Gallery in 2016, making multiple return visits. In autumn 2020, the tapestries travelled to Newlyn Art Gallery & The Exchange in Penzance, where they were shown alongside the TV series that spawned them. ‘It proved the perfect exhibition for that time,’ says programme curator Blair Todd. ‘The show broke all attendance records for the time of year and, for 34 per cent of surveyed visitors, it was their first visit to the gallery.’

A version of this article first appeared in the winter 2021 issue of Art Quarterly, the magazine of Art Fund.

Seizure, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, to 14 June 2023. Free entry and 10% off in shop with National Art Pass. Please check YSP website for Seizure opening details.

‘Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women since 1945’, Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham, to 9 January. Free to all. Then at The Levinsky Gallery and The Box, Plymouth, 26 March to 5 June. Please check websites for booking details.

Dance (All Night, London) will be included in an upcoming ACC exhibition ‘Found Cities, Lost Objects’, curated by Lubaina Himid.

The Vanity of Small Differences, Hereford Museum & Art Gallery, to 18 December. Free to all. Then at the Dick Institute, Kilmarnock. Free to all. Please check websites for the latest information on exhibition opening dates.

The more you see, the more we do.

The National Art Pass lets you enjoy free entry to hundreds of museums, galleries and historic places across the UK, while raising money to support them.