Cornelia Parker on making art as a concerned citizen and surprising collaborations

Art Fund director Jenny Waldman talks to artist Cornelia Parker about her Tate Britain exhibition, revisiting early pieces and the importance of museum collections.

A version of this article first appeared in the summer 2022 issue of Art Quarterly, the magazine of Art Fund.

Who is Cornelia Parker?

Born in 1956, Cornelia Parker studied art at Wolverhampton Polytechnic and the University of Reading. Her acclaimed work – in a range of media, including installation, sculpture, drawing, film and photography – often stems from her fascination with the histories of and the connections between objects and materials, and how they can be transformed to reveal new meanings. She was shortlisted for the 1997 Turner Prize, became a Royal Academician in 2009 and was awarded an OBE in 2010. Her Tate Britain exhibition includes more than 90 works from across her 30-year career.

Jenny Waldman: One of the new works you are working on for this exhibition is a film piece called Flag. Can you tell us about it?

Cornelia Parker: It’s being filmed in a flag factory in Swansea, and it’s all about the making of the Union Jack, but the film is run backwards. So, the flag gets dismantled and all the various pieces of material are put back on the rolls, and then the rolls are put back in their storage space. It’s something of a lament following Brexit, and the thought that the Union Jack may not exist in the future. I like to think there’s some ‘sympathetic magic’, as I call it, in there too, in that if you enact something as a sort of pre-emptive strike, then the real thing won’t then happen, because you’ve done it already.

JW: The undoing of things, the underside of things and the shadows of things are something that you’re very interested in. How do you think about that process?

CP: I do love shadows. Another new piece I’m making is a greenhouse in which all the glass panes have small strokes painted on them in chalk from the White Cliffs of Dover, a bit like chalking time. I did something similar at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, in 2018. This piece is called Island. The floor of the greenhouse will have some of the tiles Pugin designed for the Houses of Parliament [removed during its restoration], which I was given when I was the official Election Artist there, in 2017. So, the floor is the corridors of power, and the greenhouse is a vulnerable thing – perhaps like the British Isles, or the White Cliffs of Dover, and perhaps a small part is about global warming, with the ‘greenhouse effect’. There will be a light inside which pulses, like breathing, or like a lighthouse, which will cast the white chalk marks as dark shadows – warning us of the dangers.

JW: A lot of your recent work has related to the state of the nation, and the state of democracy…

CP: I’m just a concerned citizen, a bit despairing about world affairs, and that can’t help but impinge on what I make. Ever since I made Transitional Object (PsychoBarn), in 2016 [a commission for the roof of the Met in New York, in the form of a recreation of the façade built as the set for Norman Bates’ house in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho, created from materials from a traditional American red barn], after which came Donald Trump’s election and then the final Brexit date, it feels like everything’s changed.

JW: Your 2015 installation War Room will also be in the exhibition, which followed from a visit we both made to the factory in Richmond where the Remembrance poppies are made…

CP: When we visited the factory, I noticed there was this perforated material which was just rows and rows of where the poppies had been punched out by machine, and I immediately thought, ‘This is it, this is the material.’ The material itself was surplus, and the holes were absences, just like the soldiers the poppies were commemorating. The material is a negative, and so the idea was to have a double negative in the form of an empty room in which the fabric was suspended like a tent. Another reference was to the Field of the Cloth of Gold, when Henry VIII took a tent to France to meet the King to improve relations, but which never worked out. I liked the idea of calling the related film War Machine [showing the poppies being made] because it felt more active and ongoing.

JW: The survey includes early work such as Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991) – your installation of the suspended fragments of a blown-up garden shed – alongside more recent work. To what extent are the works in conversation with each other?

CP: The early work is always there with me. War Room, for example, was made as a response to the exploded shed. The shed is something you walk around and look into, whereas War Room you are inside. War Machine felt very much in keeping with the shed because neither was about war per se, but the ravages of explosions are something we see every day on the news now, so I’m sure visitors may also see those works differently.

JW: Tell us about your collaboration for Cold Dark Matter – you enlisted the British Army to blow up the shed for you

CP: The Army were very keen to help, and there were lots of moments that you only get when you’re making something with somebody who is not from the art world, which I really relish, as they’re usually so much more interesting than moments you might have in the studio on your own. Such as when the Army blew up a car to show us what the explosives could do, and said that, usually for that kind of test, they would put a dead pig in the car. I was also lucky with that work because 10 years later, after 9/11, I wouldn’t have been able to do it.

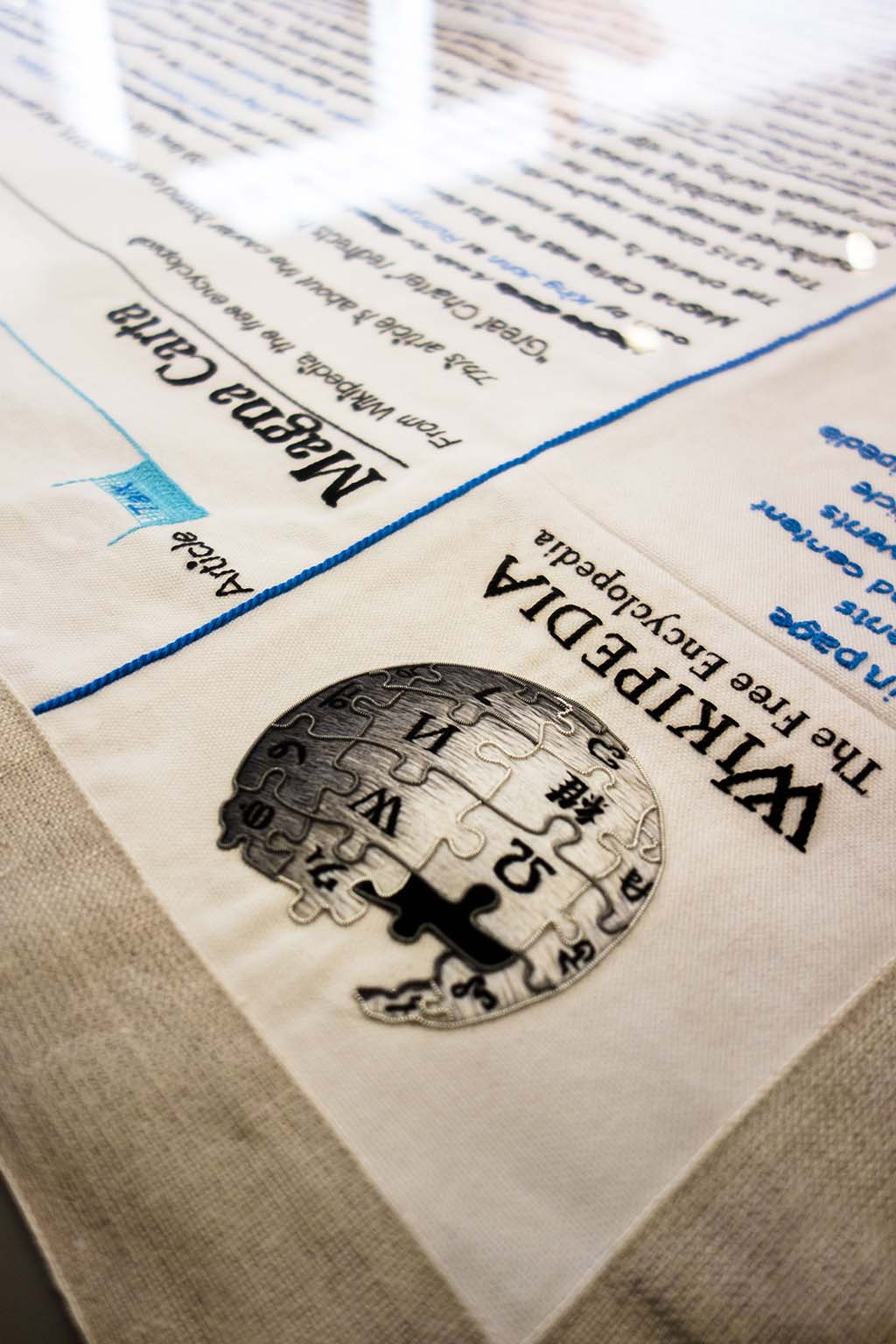

JW: Your 2015 piece Magna Carta (An Embroidery) was participatory in a different way. You asked more than 200 people, including prisoners and lawyers, to recreate in embroidery, the Wikipedia page on the Magna Carta, to mark its 800th anniversary…

CP: It was made by many hands and, like Wikipedia itself, the work was crowdsourced. There were about 46 prisoners who did a lot of the long sentences, work was also done by about 40 women from The Embroiderers’ Guild, and then some people did individual words or phrases. Edward Snowden embroidered the word ‘liberty’, Jimmy Wales embroidered ‘user’s manual’ and Jarvis Cocker did ‘common people’.

JW: Another well-known work on display will be your installation Thirty Pieces of Silver (1988-89), for which you suspended domestic sliver-plate objects that you had flattened by a steamroller, and which I think was your first ‘destructive’ work?

CP: Yes, I was living in Leytonstone at the time in a house that was about to be knocked down for a motorway, so there was this feeling of imminent threat. I think that partly went into the steamroller, that and the type of violence in the cartoon Tom and Jerry. But again, it was in the hope that our house wouldn’t get knocked down, so another example of sympathetic magic or preventative medicine.

JW: One of several of your works acquired with Art Fund support is the 2017 short film Left, Right & Centre, which you made as official General Election Artist, acquired for National Museums Northern Ireland. It shows piles of newspapers in the House of Commons, full of election coverage, swirling round each other as if caught up in gusts of wind. Were parliamentarians interested in what you were doing?

CP: David Lammy was very enthusiastic. His wife is an artist, so he was totally into it, but, aside from the House of Commons security, I’m not sure if many others knew what I was doing. The House of Commons had never been so messy. We were in there filming at night with a drone, which was fantastic. It’s important for works to be owned by public collections because I know they will be preserved and looked after well, and that people can see them. And museums are part of our history. My exploded shed, Thirty Pieces of Silver and a work called Room for Margins are all owned by Tate. I love public collections, I think they’re great, wherever they are. A piece of mine made in 2016 has just gone to the Detroit Institute of Arts. It’s called There must be some kind of way outta here, and is made from the pieces of a wooden staircase going up into the loft that was ripped out of Jimmy Hendrix’s former flat in London, when it was being turned into what is now the Handel & Hendrix museum. They were about to put it in a skip, and then they thought that I might like it.

JW: You were also, of course, an Art Fund Museum of the Year judge, in 2016. What was that experience like for you?

CP: It was great, I really loved it – we went to York Art Gallery, Bethlem Museum of the Mind and the V&A in London, Arnolfini in Bristol, and Jupiter Artland in Scotland. The V&A won that year, which was well deserved.

JW: Getting visitors back into museums is very much part of Art Fund’s mission in promoting National Art Pass membership, particularly to young people, with the Student Art Pass and new Teacher’s Art Pass pilot. What were your early experiences of museums?

CP: I didn’t go to a museum until I was 15, when I came to London on a school trip with my art teachers and we all stayed for a week in a hotel near Victoria Station. I remember coming to Tate Britain and thinking what a brilliant museum it was, and that I might get to exhibit there one day. And here we are, 50 years later!

JW: How fantastic! Your exhibition will have opened by the time this article is read by our Art Fund members. If you were giving them a tip before they visit, what would you ask them to look for or think about?

CP: Leave some time to watch the films, which aren’t very long but are very much part of the work. And also to look for works throughout the museum, as they’ll be popping up in different places.

‘Cornelia Parker’, Tate Britain, London, 19 May to 16 October 2022. 50% off paid exhibitions with National Art Pass.

Each issue of Art Quarterly contains previews, reviews, long reads and artist interviews relating to current and upcoming exhibitions at museums, galleries and historic houses across the UK, as well as news on the impact of Art Fund’s charitable programme.

Become an Art Fund member to receive four issues of Art Quarterly per year and join a community of 130,000 art lovers enjoying free or reduced-price venue entry, and up to 50% off exhibitions, with their National Art Pass. Already a member? Renew your membership today.

The more you see, the more we do.

The National Art Pass lets you enjoy free entry to hundreds of museums, galleries and historic places across the UK, while raising money to support them.