Joy Gregory and Hew Locke on history and the high seas

Art Quarterly editor Helen Sumpter talks to Joy Gregory and Hew Locke about their experiences of the Caribbean and how Devon and Cornwall have influenced their work.

A version of this article first appeared in the spring 2022 issue of Art Quarterly, the magazine of Art Fund.

Who is Hew Locke?

Born in 1959 in Edinburgh, to a Guyanese father and an English mother, Hew Locke spent his formative years in Guyana before studying at Falmouth University and the Royal College of Art, London. His largely sculptural work, using a range of mixed media and found objects, draws on colonial and Caribbean histories to playfully interrogate our cultural present. He is currently showing in ‘Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s-Now’ at Tate Britain and is undertaking the 2022 Tate Britain Commission for the Duveen Galleries. His 2019 installation Armada, comprising 45 suspended votive boats, each one unique, was recently acquired for Tate with Art Fund support, and is currently on display at Tate Liverpool.

Who is Joy Gregory?

Born in 1959 in Bicester, to Jamaican parents, Joy Gregory studied at Manchester Polytechnic and the Royal College of Art, London. Her work – in a variety of media but often employing seductive photographic techniques, and the use of research and dialogue with others – explores aspects of history, place and notions of beauty in relation to race, gender, social justice and desire. She is currently showing in ‘Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s-Now’ at Tate Britain, and has a new commission in the exhibition ‘In Plain Sight: Transatlantic Slavery and Devon’ at Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery, Exeter, which she was in the process of making at the time of this interview.

Helen Sumpter: You’ve known each other for quite a long time. How did you first meet?

Joy Gregory: I think it was in 1997 when I was about to travel to the Caribbean to make work for an exhibition called ‘Memory & Skin’ and wished to do research into the many cultural connections between Europe and the Caribbean for a ‘Photo 98’ commission. At the time I only knew Jamaica and my family in the Caribbean, and I wanted to go to investigate all the different aspects of the region, so I was put in touch with various people to talk to, and one of them was you, Hew. I came to see you at Gasworks [in London] where you had a studio, to talk to you about Guyana. The photographic series Cinderalla Tours Europe [carefully constructed images based on interviews with people in the Caribbean about their perceptions of Europe] was another work that came out of that trip.

Hew Locke: Yes, I was having a complicated relationship with Guyana then, and I’m sure I must have told you to ‘watch out for this, watch out for that, take your malaria pills’. It’s a place which I couldn’t stop thinking about, but was very nervous about, every time I was going there. Also, the politics of the place were, and still are, complex and complicated.

JG: I went to your studio and there was all this cardboard with white paint on it, and some rustling, but I couldn’t see anyone.

HL: I was making a piece which became a giant cardboard construction, called Hemmed In. It was bought by the Norton Family Foundation, and was later donated to the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM). I would have been bankrupt if I had kept making massive installations like that. Both my parents were artists and art teachers and how they struggled was one of the reasons why I didn’t want to be either. It was at secondary school, when I was taught by [distinguished Guyanese artist] Stanley Greaves, that something clicked in the brain when I was painting a hibiscus flower – that I wasn’t painting it, I was creating it, and that was the first time I figured out what creativity is.

JG: I’ve been teaching the whole of my career, which has really helped with the development of my practice – there are always new ways of thinking, new ideas, and also just having conversations with successive generations of people. For me, teaching has always been about exchange.

Our generation sense that work dealing with serious issues needs to be aesthetically beautiful, so that people will listen

HL: I stopped teaching about eight years ago, and my approach is different, but I feel the same in that it’s about trying to make a connection with somebody, and understand where they’re coming from. The most important tutorial I ever had was at the end of the first year of my degree at Falmouth in 1986, with Paula Rego. At that time I was painting the landscape, and she very gently but persistently questioned why I was doing this work, and I said: ‘I don’t really know. I’m dreaming of Guyana every night, but this is what I go out and do.’ And she said: ‘Well, you can do what you like and you don’t have to show anybody all the things you do. I mean, I kill people in my work, I chop people up.’ And I stopped making that type of work that day.

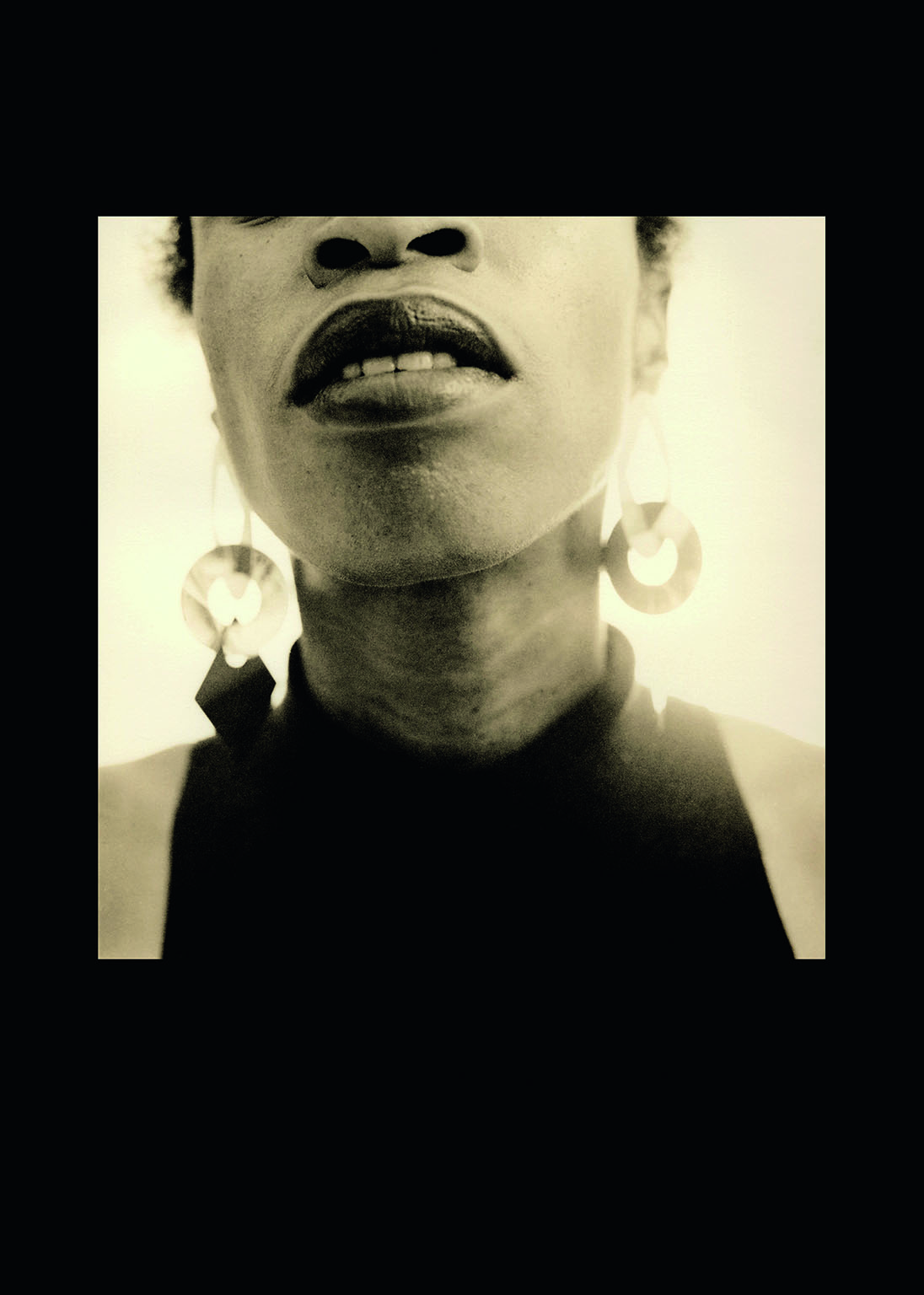

JG: Really – in some ways I think that I was unteachable because I was focused on access… but we’ve been asked to talk a bit about the exhibition ‘Life Between Islands’ at Tate Britain. The three photographic works I have in there are from Autoportrait [a series of nine self-portrait photographs, originally made in 1989-90 as a response to the absence of Black women in the fashion and beauty industry during Gregory’s youth]. Tate is also making a poster with all of the nine. They have been exhibited quite a lot, I think because it’s a particularly seductive work that also feeds into lots of people’s ideas around identity and the politics of identity.

HL: Because of my upcoming Tate Britain Duveen commission I hadn’t thought so much about my inclusion in ‘Life Between Islands’, but when I saw my four sculptures from the ‘Souvenir’ series [white busts of members of the British Royal family at the height of Empire with their identities transformed by carnivalesque decoration, including medals from colonial wars, trade beads and lots of fake gold (2019-)] in the exhibition they made complete sense. There are also sculptures by my dad [Donald Locke, who died in 2010] in the show. It’s work that I was familiar with as a child, but was quite strange to live with because I didn’t ‘get’ his work until after I’d been to art school. It was only then that I was able to figure out that it was about being a Black man living in London in the 1970s, and it was tough, you know, the humiliations he had to suffer. Though he never said that publicly at all.

JG: I think about my uncle who came over from Jamaica in the early 1960s. He went back home and lived in extreme poverty, which was preferable to the terrible treatment endured by that generation in the UK. Some people said: ‘Well, he should never have left.’ But people have their pride. And it’s still easy to forget that you have nothing to be grateful for. With our generation of artists it’s not so much about feeling grateful but sensing that work dealing with serious issues needs to be aesthetically beautiful, so that people will listen.

HL: Same thing here. I can never be overtly political in my practice. I’ve always wondered: ‘Well, is that because I was born here but grew up in Guyana, in a place where there was a Black president? I mean, in a politically and racially complex society?’ I ponder these things ad nauseam. One reason why I didn’t spend my teenage years here is because my mum, who is white, wouldn’t allow it to happen. In 1969-70 we went to school in Edinburgh, where my dad was doing a residency at Edinburgh School of Art. The racism that we experienced at school was such a complete shock that my mum decided: ‘No, these kids are going to grow up in Guyana until they’re adults.’

JG: I think it talks to the fact there is no one single experience. When I did that trip to the Caribbean, it really opened my eyes. What we call ‘Black’ here was completely different once you moved to a different location, in terms of culture and sociology. And, politically, it changes wherever you are.

HL: Class changes the whole dynamic as well. In Guyana, the main tension is between Black and Indian. The Indo-Guyanese connection is in my work a lot, but it’s a tricky one because I feel like people don’t understand, or aren’t interested in understanding, such a complex cultural and historic dynamic at all. People can be lazy. Another thing that drives me mad is that still in big Hollywood films, at some point, somebody will be driving along and a character will come into view who will be the ‘idiot Rasta’, you know, speaking this horrible accent. And there are some people who still do not see that as being racist.

I had been interested in boats since my travels to Guyana, but after a sailing trip off Falmouth Bay I became obsessed

JG: Well, it’s about stereotyping people, isn’t it? I remember when I was a student I was invited to participate in an exhibition which was about ‘Black art’. I sent my pictures in and they sent them back because they weren’t ‘Black enough’. They were interiors, because at that time that’s what I did – made pictures of interiors and still lifes. I was confused. I think, because of having grown up outside the metropolis, I wasn’t aware that my work needed to look or be a certain way. For me, it was really interesting because by building those walls around what you should and shouldn’t be, you’re doing exactly what people have decided you should be. The freedom is being able to produce whatever you like.

HL: Exactly. That reminds me of when I went to a show in about 2008-9 in New York where there was a room dedicated to African American abstract painter Jack Whitten, and it felt like it was the first time that somebody had thought abstract art by a Black artist was valid. Even further back, to my first and second year of art school in Falmouth, the head of the art-history department at that time, David Cottingham, was very aware of the lack of diversity in Cornwall and organised talks by artists such as Eddie Chambers and Rasheed Araeen. It’s very different now, but, for me, it created a particular mindset. Falmouth was also the first place I made a boat sculpture. I’d been interested in boats and ships from my travels to Guyana because to cross any big river there you need to take a boat, but it was after being taken on a sailing trip out of Falmouth Bay that I really became obsessed with them.

JG: I have exhibited at Newlyn Art Gallery & The Exchange in Cornwall, where I spent a lot of time. It was really enjoyable being in a space where the landscape is completely different. I was also aware that it wasn’t very diverse, but it also has a really long Black history, and connection with the African continent and the Americas. When I started thinking about the commission for the exhibition ‘In Plain Sight: Transatlantic Slavery and Devon’, at RAMM in Exeter, I was also thinking about the idea of the sea and looking at its collection, a lot of which is actually from Africa. And when you start looking into the history of the land and the sea, you discover things such as the port town of Topsham, just south of Exeter, which was the second-biggest port in England during the 17th century. A lot of the money generated by the port came from cloth but also from sugar, which has led to my work for RAMM. It’s in three parts – photographs, video and a big textile piece, which is talking to an 18th-century textile from the collection called the ‘Combesatchfield Embroidery’, which makes reference to the wealth of the time, and in which there’s a little figure of a Black boy holding a parasol.

HL: Yes, I know that type of image. I can’t talk about any of the details of my upcoming Tate Duveen commission but sugar plantations are something that I have also been thinking about for a while. And the whole sugar thing I find fascinating because, growing up in Guyana, once a month or so, the sky would rain ash from the burning sugar-cane fields. If you’re Guyanese it’s a romantic idea to go to the market and order some cane juice. But then you realise that the land you’re walking on was literally built by slavery. What we used to refer to as the ‘backdam’ – the earthworks several miles inland to prevent the land getting flooded – was built by enslaved people for the Dutch, who reclaimed all the agricultural land from the sea.

JG: The textile piece I am making will look quite naïve and uses a large cyanotype print of hair, which looks like the sea. It flows from the Caribbean and the Atlantic countries all the way down to the sugar production in the factories in this country, which exploited a different group of people. So, it’s the story of sugar and is called The Sweetest Thing. One of the other things that’s really interesting about the Southwest is how many people from there owned enslaved people in Guyana. Guyana, Barbados and Jamaica were the three places where there was the most ownership of enslaved people at that time by the population of Southwest England.

HL: Sometimes you don’t see these things. It’s like when I became interested in statuary, after seeing the dumped statue of Queen Victoria that had been taken down from outside the law courts in Guyana in the 1970s, after the country became a republic. As a teenager, I was shocked because it was an act of sacrilege, but then I started thinking: ‘Who are these people, and why are they up there?’ When the statue of Edward Colston was pulled down in Bristol in 2020 it was more edgy because that statue was generally reviled in Bristol. But Colston, for me, was also fascinating because I had destroyed a photographic image of him in 2006 by screwing and fixing objects such as cowrie shells and fake jewellery onto it to make him into a fetish, using symbols of what he’d done.

JG: Yes, it’s like the statue of General Redvers Buller in Exeter. There was a huge debate over that but it ended with the mindset that you leave it up, but you put something there to say exactly what he did.

HL: It’s tricky. I’ve been on a number of panels about this subject, as you can imagine. Another interesting aspect about the Colston statue being taken down was that it was about 150 metres away from the cenotaph in Bristol, and all of a sudden there was a big rally by people who had got the completely mistaken idea that somebody was going to attack the cenotaph, crying: ‘Defend our country.’

JG: Those things can be both painful and infuriating. The country belongs to all of us, as does our shared history, and we should be showing both sides of the mirror.

‘In Plain Sight: Transatlantic Slavery and Devon’ Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery (RAMM), Exeter, 29 January to 29 May 2022. 50% off exhibitions and 10% off in shop and café with National Art Pass.

‘Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s-Now’, Tate Britain, London, 1 December 2021 to 3 April 2022. 50% off paid exhibitions with National Art Pass.

Hew Locke, Armada, Tate Liverpool, 15 February 2022 to 2023. 50% off exhibitions with National Art Pass.

‘Tate Britain Commission 2022: Hew Locke’, 23 March 2022 to 22 January 2023.

Each issue of Art Quarterly contains previews, reviews, long reads and artist interviews relating to current and upcoming exhibitions at museums, galleries and historic houses across the UK, as well as news on the impact of Art Fund’s charitable programme.

Become an Art Fund member to receive four issues of Art Quarterly per year and join a community of 130,000 art lovers enjoying free or reduced-price venue entry, and up to 50% off exhibitions, with their National Art Pass. Already a member? Renew your membership today.

The more you see, the more we do.

The National Art Pass lets you enjoy free entry to hundreds of museums, galleries and historic places across the UK, while raising money to support them.